PASSAGES – Walter Benjamin, a suicide, a monument, a film. 2006

PASSAGES

a suicide, a monument, a film

It’s not very often that one comes across an absolutely stunning contemporary public art work. For those interested in such things head off immediately to Port Bou, a small Catalan town on the Mediterranean coast of Spain. Hannah Arendt described the setting as one of the most beautiful she had ever seen. But the town itself is not beautiful. It used to be a customs town from which it derived most of its income legitimate and otherwise. Its vast railway yards, replicated in Cerebere, the French customs town across the border, attest to its former importance. In the 1970’s I took a train from Barcelona to Paris. It stopped in both Port Bou and Cerbere for customs inspections, and to change trains since the railway gauge was different in France. When Spain joined the EU Port Bou’s economy collapsed. Now it’s after tourists and a brand new, EC funded marina has been built. But Port Bou is famous, or should that be, infamous, for being the place where the great German Jewish philosopher, Walter Benjamin, committed suicide.

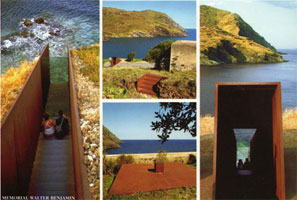

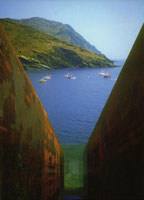

In the summer of 2004 I was on holiday with friends in Port Vendres in France where Charles Rennie Mackintosh spent the last four years of his life drawing and painting. Like most other cultural tourists we headed into northern Catalonia seeking the Dali experience. I had insisted that I would want to stop in Port Bou on the way back to pay my respects to Benjamin. I had an idea that there was some kind of memorial to him but thought it might just be a plaque. We left Cadaques and Dali’s house and studio (which by the way has a Mackintosh card table from one of his tearooms) and headed north for Port Vendres. I was driving the leading car and, as we dropped down into Port Bou in the early evening dusk, I caught sight of a sign, ‘Walter Benjamin Memorial’. I turned sharp right and up a narrow road hoping that the following car had seen my sudden manoeuvre. The road snaked up to a cliff-top cemetery. Last to get out of the cars, I was greeted with, ‘WOW! LOOK AT THIS!’ We stood in awe and wonder at what lay before us – a corten steel tunnel that cut into the ground, passed through the cliff edge and came out overlooking the sea. About a hundred steps lead you down and as you descend you see ahead rocks lapped by the swirling sea. A few steps before tumbling out at the end there is a sheet of plate glass; inscribed on its surface, in several languages, is a Benjamin quotation;

IT IS MORE ARDUOUS TO HONOUR THE MEMORY OF THE NAMELESS THAN THAT OF THE RENOWNED. HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION IS DEVOTED TO THE MEMORY OF THE NAMELESS.

The sculpture, ‘Passages’, had been made by the artist Dani Karavan in 1995. The light had gone and we decided to return the next day to photograph the work, spend some time there and visit Benjamin’s grave in the cemetery.

On our return we also discovered, in a rundown building, a small archival exhibition containing material related to Benjamin’s death and the setting up of the memorial. Large portraits of Benjamin and Karavan, flanked the entrance. The archive papers were pinned to a number of ‘A’ frames with their titles in Catalan and all were yellowing and dusty. Language deficiencies made it difficult for us to get the most from the material displayed. I began to wonder who this archive was for. It was my first feeling that Port Bou was not quite sure about how to handle the death in its midst of one of the great philosophers of the 20th century. My special area of interest is public art and I have photographed many works all over the world. I had met Dani Karavan, visited and photographed a number of his works and included them in my lectures on public art. This memorial had been completed in 1995 and I wondered now how I had not come across it in books or magazines. Well, maybe I was not looking hard enough. But it does seem surprising when I now regard it as one of the great public art works of the late 20th century.

Months later the archive, and a lack of knowledge about the memorial sculpture, still troubled me so I wrote a letter, translated into Catalan, to the Mayor of Port Bou offering to give my services to improve the archive by, at the very least, getting all the titles translated into several languages. The reply, when it came, was from a Senor Vancells who had responsibility in the Ajuntament (town hall) for the Benjamin legacy. It may have had something to do with the poor English into which it had been translated, but the gist of it was they were not interested. It also said words to the effect that, ‘We do not know why Walter Benjamin chose to die in Port Bou.’ This seemed at odds with all I had read about the events of the 25 and 26th of September 1940.

The story of his untimely end is now well-known. Having moved to Paris in 1933 to avoid Nazi persecution, he was again under threat when the German forces were about to take Paris. Like many Jews and others fleeing Nazism he moved south looking for an escape route. With documents ensuring his access to Spain and a visa for the USA he proceeded with two others to the French town of Banyuls, a few miles from the Spanish border. However to cross the border it was necessary to make a long detour, on foot, across the Pyrenees and then proceed to join the railway at the Spanish town of Port Bou. There the Spanish authorities raised some issues about the group’s travel documents. There were problems and were told they would be returned to France, and certain arrest, the following day. They were put under ‘house’ arrest in the Hotel Francia. Benjamin was an asthmatic with heart problems and he carried a supply of morphine for self-medication. He was not fit and he carried a large briefcase filled with his papers, manuscripts and notes. He was found dead the next morning. After his burial in the cemetery in Port Bou his companions were allowed to continue their journey and eventually reached the USA.

The route taken to escape from France had been used just two years before by Republicans escaping from Franco’s armies INTO France. It was known as Route Lister, named after the republican general who organised the retreat. Benjamin’s guide was a young Jewish woman Lisa Fittko. Raised in Vienna and Berlin, she had also made it south and was living between Port Vendres and Banyuls. She had learned of the route over the Pyrenees from the socialist mayor of Banyuls and Benjamin came to see her to ask if she would guide him and his two friends over it. In her autobiographical memoir, ‘Mein Weg Uber Die Pyrenaen’, she says, ‘Benjamin travelled slowly and steadily; at regular intervals – I think it was ten minutes – he halted and rested for about a minute. Then he continued on at the same constant pace. As he told me, he had thought it all out and calculated it during the night: “I can go all the way to the end using this method. I stop at regular intervals – I must pause before I am exhausted. One must not completely overspend one’s strength.” This was the first of many trips over the next seven months that Fittko undertook guiding many refugees to safety. When it became impossible to continue she and her husband finally escaped. She lived the rest of her life in the USA dying in Chicago in 2003 at the age of 94.

Gershom Scholem, in his book on his relationship with Benjamin, ‘The Story of a Friendship’, says, ‘After all I have told here it is evident that Walter repeatedly reckoned with the possibility of his suicide and prepared for it……Despite all the astonishing patience he displayed in the years after 1933, combined with a high degree of tenacity, he was not tough enough for the events of 1940.’ From the beginning doubts have been raised about the actual cause of Benjamin’s death. The notes of the doctor who attended the scene and the death certificate are inconclusive. There is even a recent film entitled, ‘Who Killed Walter Benjamin?’ which adds further to conspiracy theories. Fifteen days after Benjamin’s death his companion, Frau Gurland, wrote in a letter to Theodor Adorno, ‘At 7 in the morning… (I) was called down because Benjamin had asked for me. He told me that he had taken large quantities of morphine at 10 the preceeding evening and that I should try to present the matter as illness; he gave me a letter addressed to me and Adorno. Then he lost consciousness. I sent for a doctor, who diagnosed a cerebral apoplexy; when I urgently requested that Benjamin be taken to a hospital….he refused to take any responsibility since Benjamin was already moribund.’ For myself it remains the suicide of a man who knew the consequences of a return to France. His struggles to keep going and to survive ended in Port Bou.

2005 was the 65th anniversary of Benjamin’s death and I wanted to do something to mark this. I can’t walk too well and I needed a collaborator. I thought that another artist, with an interest in Benjamin, might walk the route over the Pyrenees with a video camera and make the journey as a performance to camera reflecting on Benjamin’s life and work. Ross Birrell a friend and colleague was that person and we began to plan a visit to Port Bou on the dates of the anniversary. I wrote to Vancells asking if there were any plans to mark the anniversary but received no response. I went on the Catalonian and Port Bou tourist websites and hit, ‘Events’. For Port Bou….zero, nothing. We decided therefore that Ross would do the walk; we would film it and the sculpture and to make our own events to mark the anniversary. It seemed a good enough idea to get something special out of it. We checked into our hotel in the evening and after a meal on the promenade we wandered past the tourist kiosk and found, to our astonishment, that it was plastered with posters – EVENTS TO MARK THE 65TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEATH OF WALTER BENJAMIN. The events included a musical recital with flute and guitar accompanied by readings from Benjamin’s writings, and re-enactments of his arrest, his last evening and interment. We couldn’t believe our good fortune.

The film was shot on a basic digital video camera, hand held and with a tripod. Only the footage that was shot has been used. Only the sounds that were captured have been used. No other material has been cut into it. What you get is what we got.

Of the re-enactments which make up about half of the film, several elements stand out; the flute music by Anton Serra, which accompanied each section and which, with one guitar piece by Jaume Torrent, make up the music; the interment when the actor, Isidro Gubert, walks slowly and hesitatingly into the depths of the sculpture; the closing recitation by Montse Vives of Fernando Pessoa’s poem, ‘Afinal’. There are numerous references to Benjamin’s thinking in the film including his thoughts on the painting, ‘Angelus Novus’ he had bought from Paul Klee and the notion of a storm ‘blowing from Paradise’.

The great spirit of serendipity seemed to be weaving its spell of good fortune on us. How else can one explain that as the day of the re-enactments progressed a storm was brewing. At the very moment of the recitation of the Pessoa poem, itself containing references to storms, the wind blew fiercely, the sky darkened and black clouds scudded across it while, below the cliff, the sea was being whipped up. As Montse Vives delivered the poem with powerful, emotional expressiveness, her long hair was blown across her face and at one point she seemed to stumble and had to regain her footing. And the Pessoa poem, ‘Afinal’ – ‘After All’ – in keeping with many of his poems it was attributed to one of his heteronyms, in this case Alvaro de Campos, whose fictional biographical details included that he had ‘trained as a nautical engineer in Glasgow’! And Madeleine Claus, whom we met by chance in a cafe after one of the events, a professor of German at the University of Perpignan, she had met, and interviewed, Lisa Fittko and had been involved in the commissioning of the sculpture.

The Mayor of Port Bou attended the events and at the wreath-laying ceremony at Benjamin’s grave he gave an address. Looking at him he seemed to indicate that if he could have been anywhere else at that moment he would have preferred it. This was in absolute contrast to the address of the Mayor of Banyuls whose stirring address, knowledge of Benjamin and the implications of the events that took place in Port Bou on the night of the 26th of September 1940, left one in no doubt of its profound importance. Before leaving Port Bou I went into the general store to stock up on my supply of postcards of the sculpture. The store is owned by the Mayor who pressed me to take some new tourist brochures of Port Bou as if to say – there is more to this town than the memory of Benjamin’s fateful visit.

It seemed that we were the only non-Spanish/Catalan people attending the events and wondered why this was so. We introduced ourselves to Senor Vancells who was very friendly and helpful. Mysteriously he had not received my last letter. He and his council had put money, and a lot of effort, into preparing the events which were powerful and moving and all of the highest professional standards. Was all this effort only for a local audience? Maybe so and maybe one could argue that this is as it should be. Nevertheless it merited a wider audience. Our film now does that.

May 2006

Film: ‘Port Bou – 18 Fragments for Walter Benjamin’, DVD, 30 minutes, by Ross Birrell and David Harding.

images

|

|

|

|

PASSAGES*

|

|