published in the

THE HERALD, NOV IST 2001

‘SEARCH FOR SLOW TAKE ON WAYNE WORLD’

David Harding travels way out west to watch Douglas Gordon’s compelling view of a classic American movie.

The plan was to go to Los Angeles to attend Douglas Gordon’s major exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, MoCA, then head for the town of Twenty Nine Palms, in the high desert 45 miles north of Palm Springs, to witness the installation of ‘5-Year Drive-By,’ a work based on a similar strategy to his famous, ’24 Hour Psycho.’

As in the Hitchcock, the film is played at the speed that matches the narrative. In John Ford’s, ‘The Searchers,’ the lead character, Ethan Edwards, played by John Wayne, takes five years to find his niece after she has been taken by Commanches.

My own odyssey was planned to begin on September 12th but the events of September 11th put paid to that. The MoCa private view planned for the 15th had been cancelled as a mark of respect but the ‘5-Year Drive-By’ opening was to go ahead.

Gordon was in the second graduating year of the then new department of Environmental Art at Glasgow School of Art, so I had a particular interest in getting to the opening. Flying out on September 20 to Los Angeles, it was a four-hour drive to Twenty Nine Palms.

When Gordon arrived, we went to view the work. Nothing had prepared me for this. It was dark as we walked up to the huge screen set in the desert scrub some way behind the inn. It was stunning. A head and shoulder shot of John Wayne filled the screen, the very moment when he at last meets Chief Scar (not seen) who had taken his niece all these years before. I stood mesmerised and soaked in the detail. The intricate weave of Wayne’s cowboy hat, the fine check on his shirt, his neckerchief, his staring, steel-blue eyes, the gnarled, chiselled, confrontational expression on his face.

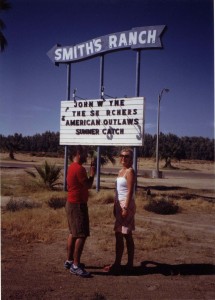

Next day we had a picnic lunch in the Joshua Tree national park and on our way back Gordon wanted to check out the drive-in cinema where the film would be shown as John Ford had intended. The run down signboard advertising the evening’s films read, ‘JOHN W YNE IN THE SE RCHERS.’ The owner had obviously run out of ‘A’s. It was worth a photograph. As we were messing about we spotted the missing letters on the ground below the signboard. They had been cut out of cardboard, stuck on the board and had fallen off in the heat. Suddenly we were aware of a black four-wheel- drive that had driven off the road up to us. Gordon went over to see what the driver wanted. He turned out to be the owner of the cinema and was very angry at our antics. Maybe we had climbed up the signboard and knocked off his carefully stuck on ‘A’s. He demanded them back and drove off at speed over the rough ground. This was a bad omen, as it seems that this man had been difficult to work with. And sure enough for some unaccountable reason he later tried, unsuccessfully, to make a last minute change to the time of programme

People started arriving from LA for the formal opening and, as the inn was booked out, many of these Angelinos were making a seven hour round trip. More than 100 people gathered at the screen just before dusk. The film was playing but the screen was still white and showed no image. Slowly, against a clear, pale blue sky and a diagonal ridge of mountains behind the screen, cutting it in two, John Wayne appeared – virtually the same image as the night before. At one frame every 20 minutes, the only change in an hour of viewing was the slightest movement at the end of his neckerchief. After the formalities, Gordon said a few words on the genesis and ideas behind the work, answered some questions and then we made our way into town to the drive-in cinema. This was a first visit for me to this disappearing US cultural phenomenon and I was not disappointed. We found a good spot, switched off the engine and tuned in the car radio to the soundtrack.

I had seen ‘The Searchers’ in the cinema when it was first released in the fifties and it became one of my favourite westerns. Since then, I had seen it on more than one occasion on television. Nonetheless I was thoroughly absorbed by the film and relished the ‘drive-in’ experience. Gordon knows that, as with ‘Psycho,’ we are so familiar with the plot that it is not difficult to engage with his re-presentation of it even at the speed of one frame every 20 minutes.

The Wayne character is implacably hostile to the Indians and is determined to kill his niece for becoming ‘indianised.’ Stories of the kidnapping of white settlers by Indian peoples, and their assimilation into Indian cultures, run right through the history of North America from the time of the first settlements. In 1704 Eunice Williams, a girl of seven, along with her father and brothers, is taken by Mohawks from Massachusetts to Canada. Except for Eunice they are all released after a few years. She forgets her native language becomes absorbed into Indian lifeand marries a young Mohawk. Despite numerous pleadings, meetings involving the governments of Britain and France at the highest levels and 60 years of prayers for her redemption across the whole of New England, she remains by choice an Indian.

To be taken by the ‘savages’ and to become one of them was the worst of all possible fates. A simple reading of ‘The Searchers’ plays on these same fears and attitudes but Gordon argues that what John Ford has done, and this in the fifties, is to make a redemptive film. The Wayne character, he says, is the savage. He kills Indians at every opportunity – even against orders as they are retreating. He kills their buffalo with abandon to deny them food. He scalps Chief Scar. But in the end he gathers his niece in his arms and takes her home.

In a recent observation Joseph McBride concludes: “‘The Searchers’ critically examines the white supremacist assumptions on which the western genre and the country itself was based, making it as profound a study of racism as Mark Twain’s ‘Huckleberry Finn.'” In fact a film for now, for right now, with a timeless message.

We all repaired to the bar at the inn and when that closed a few of us moved back up to the screen suitably equipped with a supply of drinks. John Wayne was still eyeballing Chief Scar; the coyotes were yelping in the distance, the tumbleweed was blowing, all beneath a canopy of brilliant stars in the clear desert night sky. Gordon couldn’t resist declaring at that moment the adage of the Environmental Art department that the context is indeed half the work.

We began to sing some well-known American folk and western songs from ‘Shenandoah’ to ‘Buttons and Bows.’ Gordon and I like to harmonise and Chico the projectionist, a grizzled graduate of the San Francisco Art Institute, joined us. He had a marvellous basso profundo.