The Art and Buildings department of the city of Zurich decided that it would like to acquire this work and to make it permanent using bronze letters.

Author: dharding

Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson

From time to time I used to ask my new, incoming students if they had heard of Paul Robeson. Each time there was silence – no one had heard of him. I found this strange if not disconcerting. Paul Robeson was, of course, the acclaimed American college football player, a star actor and opera singer. He was a towering international figure who had dedicated a lot of his life to the causes of the working class, civil rights across the world, and of the African American.

I became aware of him in my teens listening to his powerful bass/ baritone voice on the radio. He was a popular performer on record request programmes. This awareness grew while at art college and when, in 1960, he was billed to sing at the Usher Hall in Edinburgh I managed to get a couple of the last tickets in a sold-out event. I know these were some of the last tickets because they were for the choir stalls at the back of the stage which meant that I was looking at his back for the duration of the concert. However, I was in the front row which made it easy for me at the end of the concert to go up to him and get him to sign the back of my ticket. I still have it. One song he sang was about ‘the Sharpeville Shootings’, a recent massacre of black South Africans by the Apartheid regime. This was typical of the man and a feature of his whole life’s work.

I only learned, much, much later that this performance was part of a world tour by Robeson, the first for five years during which time he had been held in the USA in internal exile. His passport had been confiscated by the US Government. During these years Robeson still managed to give concerts to the world.

While staying in Britain in the Thirties he had befriended many trade unionists and built a special relationship with Welsh miners. He had grown to love Welsh singing and especially the male voice choirs which abounded. He sang their songs often in the Welsh language as he did with songs in many other languages. Not to be outdone by the US authorities he organised a concert for the Welsh miners using radio telephone equipment. It was reported that around 5000 miners turned up in Porthcawl to hear him sing through a loudspeaker set in the middle of the stage. He repeated this way of performing to his fans on several other occasions. However, for me the most dramatic performance took place on the US border with Canada. The unions in British Columbia invited him to come to a place called ‘The Peace Arch’ and with Robeson on the US side and the audience in Canada he delivered his concert.

In January 1976 I was in Chicago when it was announced that Robeson had died. I was on a lecture tour while also documenting public art works in the USA. I was being hosted by the Public Art Workshop that had produced a number of political murals involving local communities and based in the West side of the city. It’s founder was Mark Rogovin who later founded The Peace Museum in the city. Mark’s father was a well-known socialist photographer. ( He had, remarkably, made a suite of photographs of Fife miners.) In this milieu of social activism I found myself taken by a group of people, communists, if not by name, to a hastily arranged event in a theatre to mark Robeson’s passing. It was a memorable night of songs and speeches.

On Singing

I have been asked on many occasions what we actually taught the students in the Environmental Art department at Glasgow School of Art. I usually replied, half in jest and tongue in cheek, ‘singing,’ and proceeded to quote a short three-line poem by Adrian Mitchell in which I’d changed only one word – ‘singing’ instead of ‘poetry’- but the meaning remains the same:

Letter to a politician.

I have read your manifesto with great interest

But it says nothing about singing.

This ‘singing thing’ is not unique. It has always been a part of university undergraduate life in one form or another. Yale University has a strong tradition. With Cole Porter as president of their Glee Club in 1913 how could it be otherwise. A recent tour by a huge alumni choir elicited; ‘Anyone who has sung in the Glee Club feels part of a family………We estimate that nearly half of all present-day undergraduates sing……I would say that Yale undergraduate culture is largely based on singing.’

Douglas Gordon’s comment that he was taught, ‘To sing. Not how to sing, but simply TO sing’ described a prevailing attitude in the department. Not everyone of course can, or feels inclined, to actually sing publicly in company, but I learned from my family upbringing, and in successive other situations, the value of a few drinks and a ‘sing-song’ in forging a close and friendly social setting. Where there is mutual and supporting respect for the efforts of the individual, a confidence is bred in which people do perform whether it be a song, a poem, a story, whatever takes their fancy. That for me is singing. As the poet Shelley said, ‘social enjoyment in one form or another is the alpha and omega of existence.’

One tradition of the department took place in the last week of the Christmas term when we visited The Drover’s Inn north of Loch Lomond. This event served a number of purposes. An end of term party is a universal activity, so nothing unusual about that. Going somewhere as a group too is not unusual. But this was in many ways so much more. Once or twice we went to Glencoe first. For many students who had joined the course from other parts of the UK and abroad this was their first experience of the Scottish Highlands. It was also the case that many Scottish students had also never been there. Glencoe is stunning and of course soaked in a bloody history. On the way there a stop at Rannoch Moor to absorb the ‘prehistoric’ landscape and the site of Josef Beuys’ performance of his ‘Kinloch Rannoch Symphony,’ added to the mystery of it all. We headed back south and around mid-afternoon arrived at The Drover’s. It was quiet at that time of day and at that time of year, so we virtually took over the whole bar. This we did with the nod of the owner who was happy to accommodate 40/50 students out to celebrate. As is the case with this kind of thing, it starts slowly and as the drink begins to take hold singing and dancing break out. Nothing unusual about that either, but for these kinds of events to become memorable it has in some ways to be orchestrated otherwise it just becomes any other drunken pub night. By inviting people to sing their favourite songs or recite a poem, all the time insisting on the attention of the rest, it works. The old adage of, ‘One singer, one song,’ actually does work. One has to lead it too so that when a gap appears and the whole thing seems to be going off the boil, one has to be able to step in and do the business oneself! Many well-known songs are sung and some are perennial favourites and some others lend themselves to harmonies so the group would be in full song. The piano, utterly out of tune but it did not matter, was played. The Landlord put on dance tunes and dancing would break out. I always insisted that the coach set off back to Glasgow at around 8-00. After five hours at the Drover’s people were not too drunk and the whole coach sang as it twisted its way down Loch Lomondside. On one occasion, having got everyone on the coach, I felt a desperate need to get a drink for the journey back. I had a plastic cup so went back to the bar to get it filled with whisky. I stood next to an elderly couple that I had noticed earlier sitting at the bar and said, apologetically, that I hoped that we hadn’t upset their quiet early evening drink. The reply stunned me. “Oh no…. not at all we loved it ….. we heard some of our favourite songs. We were here last year!”

The most evocative description I have read about this experience of singing and the notion of ‘one singer one song’ is that by Laurie Lee in his book, ‘I Can’t Stay Long – Voices of Ireland’.

‘What followed was typical of other bars I went to in Galway, Kerry and Cork – something halfway between a wake and a wedding, half celebration, half common grief. The fiddler began with some horse-fair reels, then the piper took his turn. Then one by one, as the finger pointed, each man in the bar sang a ballad; old men with the slurred incantations of bards, young men with hot fruity tenors, each singing, eyes closed, reaching back in his mind, songs which smelt of the very skin of Ireland.

This was not the boozy wail of the usual pub singsong but a haunting restatement of identity. The songs I heard that night were heard in silence, or with little murmurs of approval. And they were almost all of them cries of loss – lost love, a lost cause, the loss of Ireland itself, parting, departure, death. ……………. they had that bite of melancholy at the heart of all folk song, celebrating a beauty too brief to bear. The night was long and deep; everyone took his turn……………’

Like most other art schools that are not in London, an annual London trip is more or less ‘de rigeur.’ On one return trip in October, fuelled with a goodly amount of booze from an off-licence near Euston Station, half the group, determined smokers all, occupied a section of the only smoking compartment on the northbound Virgin train. In due course after an hour or so into the journey the first songs, jokes and stories began. Soon some of the other passengers were joining in until we had a thoroughgoing sing-song. From time to time the odd smoker, trapped in the ‘no- smoking’ section of the train, would appear in the compartment, have a smoke and then disappear back to their seats. Our gallus female students, and there were two in particular for whom the term gallus was surely invented, would set upon these nicotine freaks and demand a song. One or two obliged and got such a rousing applause for their efforts that they went back to get their luggage and joined us for the rest of the journey. By now others had gathered round us from among the smokers, sitting on armrests or standing in the aisle. No matter how good or poor the song and the singing, all efforts were met applause. One of the nicotine freaks in particular was lionised by our gallous girls. He was, one could surmise, a business-man, short in stature and balding but he knew some good Scots and Irish songs and sang them with a good voice. We shared our booze with him and by the time we reached Central Station in Glasgow he, like all of us, was the better or worse of a drinking bout. His son had come to meet him and was standing at the end of the platform no doubt expecting a rather tired, maybe a little testy, father. Not a bit of it. Arm in arm with our gallous girls he strode done the platform eager to introduce us to his bewildered son and share with him this memorable journey. I’m sure the son was embarrassed – didn’t really want to know and just wanted to get his tipsy dad into the car and get home. Not only had our gallous girls won over our bedazzled businessman they had insisted that he must join us on our next visit to the Drover’s. I thought ‘Yeah, that’ll be right.’ However, a week or so later I got a letter from him;

Dear David,

Phew! What a night! There was I tired, weary, fed-up…….. I came up the train for a quiet smoke and suddenly found myself thrust into and surrounded by a wonderful group of people intent on enjoying themselves and trying to pass some of that enjoyment on to others…………………… Anyway I must commend you for exposing your students to the great art of self-entertainment……in your leadership by example…let your group know that they were most impressive, nice friendly relaxed people….evidenced by the way in which they so easily welcomed strangers into their company…….etc etc

Thanks for the memory!

Yours etc

In December, as the time for the Drover’s trip came around, our gallous girls got in touch and asked him to join us. He was up for it and asked if he could bring his brother along too! Our friend ran an Estate Agent business in the western fringes of the city. This was ideal as our coach could pick him up en route. The office was a shopfront and I cannot imagine what the staff must have thought as a fifty-seater coach pulled up outside full of young art students. I went in. The all-female staff were obviously unimpressed at thought of their boss being taken away for a day of drinking by a bunch of artistic wasters. ‘Is…….around? I arranged to meet him here’, brought an unsympathetic and equivocal reply like, we heard of this and think he’s gone doolally! I went outside and soon a Mercedes saloon drew up and our friend and his brother got out. I was introduced to the driver, his wife. As we drove off, his staff crowded at the office windows shaking their heads. We had a great time at the Drover’s that day. Our guests sang a number of songs and seemed to have as good a time as the rest of us.

Coach and train travel to field trips, as I’ve described, provided the right ambience for singing. The coach is of course exclusive as only we are in it. The train on the other hand is shared with others and the most memorable singing event, reports of which even made the BBC Radio 4 Today Programme and The Times newspaper, happened on a train.

We knew this was going to be a special journey when I managed to get First Class return tickets to London at £29-00 each under a scheme called ‘Virgin Groupies.’ What I did not know was that meals, snacks and beverages were complimentary so much so that I brought food for the journey south. The tables were set for breakfast and I said I wouldn’t be having it as I had food of my own and certainly did not want to pay the outrageous price normally charged on trains. My colleague, Peter McCaughey, who, due to our very early start, probably hadn’t eaten anything since getting up and rushing to catch the train, scrutinised the menu being tempted by the prospect of a tasty, cooked breakfast. ‘It says here that it’s complimentary.’ I looked at it but doubted it so when the waitress appeared Peter enquired if breakfast was indeed free? She replied with some disdain that that is exactly what the word ‘complimentary’ meant! For our return trip we gathered at Euston Station in good time for our 5-30 departure. It was a Friday and the First Class compartments were crowded but we all had booked seats. All of us were easily distinguishable from the normal ‘suits’ in First Class and those passengers who arrived late and had not booked a seat began to complain to the train staff in terms like, ‘Who are these people? Surely they are in the wrong section of the train? Could you remove them? We paid for First Class travel and cannot get a seat!’ The train departed with threats in the air. We got to Milton Keynes in an hour but the train did not depart for some time. By now dinner was being served and the wine was going down a treat. So what…. delays often happen. After getting on the move again and, as the train struggled up to Rugby, word began to circulate that there had been an accident further up the line. Then it was confirmed; there had been a derailment at Stafford and the train would not move until the line was cleared or another route taken. The Virgin staff were fantastic for this was the signal to wheel out the drinks trolleys in an attempt to keep the customers happy. When I saw that the ‘suits’ were rapidly clearing the trolleys by taking handfuls of beers, gin and whisky miniatures with appropriate mixers I had no qualms myself in doing likewise. The students of course were well-used to making the most of such situations. The mood in the compartment became convivial and when I heard the first notes of a song coming from one of the ‘suits’ that was my signal. I joined in and soon a full-blown singsong was taking place. More drinks and snacks were provided. Solos were being sung with panache and groups were rendering their favourite rugby songs with great gusto. We were still outside Rugby station but it didn’t matter as we were all having a great time. It was at this point that Peter said, ‘You should see what’s going on in the next compartment….the students have got the passengers to make drawings of Richard Branson!’ I hurried along. The place looked like a primary school drawing class. The large paper dinner mats had been turned over and used for drawings which been taped on to the windows and hung from the luggage racks all around the compartment. True to the singing tradition, the passengers had also been encouraged to write the title of a song appropriate to our predicament. So next to images of Branson were, among many others; ‘Help,’ ‘Homeward Bound,’ ‘By the time I get to Phoenix,’ ‘Show me the way to go home.’ The last one was enough to get me started and the whole place was soon in song. At one point a silver-haired, elderly and distinguished looking man came up to me and said that this was one of the most enjoyable train journeys he had ever been on. He praised the students; couldn’t say enough about how wonderful they were. And then he said with astonishment in his voice, ‘Look, over there is a brain surgeon, that one there is the chief executive of a company, that one over there is a QC, and they are all singing. You must get on to the media about this. It’s just too good a story!’ In the haze and daze of it all I can’t remember exactly where we had got to at this point. Crewe maybe and the train was now running four or five hours late. At one station one of the ‘suits’ didn’t want to leave the train as he was having such a great time that his mates had to drag him off before it departed. The Virgin staff had by now given out all the drinks and food. However, I had a litre of Jameson’s stowed away in my bag ready for just such a situation. The Jameson’s was flourished like a conjuror taking a rabbit out of his hat and this kept us going for a bit more of the journey. We rolled into Glasgow Central at 3-45 am on the Saturday and, still high, marched into the Station Master’s office to pick up our refund claim forms for being five hours late. The cheek of it!

I got into the art school on the Monday morning to find the drawings pinned up in the studio and copies of an article in The Times with the headline ‘Delayed Virgin travellers adopt a party line!’ Some people had heard an interview on the Today programme with one of the ‘suits.’ I wonder if it was the silver-haired one? Some weeks later Virgin sent a cheque refunding the whole cost of our travel!

But since it falls unto my lot

That I should rise

And you should not

I’ll gently rise and softly call

Goodnight and joy be to you all”

From: The Parting Glass

‘Other Voices, Other Rooms’ – Zurich, Nov. 2021

Ross Birrell and I were among several other artists commissioned to make works for the new Zurich City Police building at Muhleweg. Under the title of ‘Other Voices, Other Rooms’ curator Adam Szymczyk’s proposal was for the works to be temporary, each of which would be documented through photographs and texts. These would then be exhibited in the completed building after it had been formally opened and would remain as an ‘exhibition’ of all the works undertaken.

Being a police authority building Ross and I decided to work with a statement of Roman law which forms the basis of many contemporary legal systems – for Ross, ‘Audi alteram partem’- ‘Listen to the other side’, and myself with a variation, ‘Audiatur et altera pars’ – ‘Let the other side be heard as well’. Ross’s work consisted of making videos of improvised performances by two musicians and a singer in the prisoner cells in the building.

David Harding, Audiatur et altera pars (2021)

Text installation in copper leaf in five languages.

LL Ruder Plakat font: provided by Lineto GmbH, Zurich

On the pavement at the entrance to the new Zurich Police Authority building on Muhleweg the maxim ‘Audiatur et altera pars’ (Let the other side be heard as well) is installed along with translations in the four Swiss national languages. It is a general principle of rationality and was treated as part of common wisdom by ancient Greek dramatists. It forms part of many contemporary legal systems.

The phrases are written in the font “LL Ruder Plakat” which is used for the first time in a public context. This homage to Emil Ruder, type designer and lecturer at Academy of Art and Design in Basel, points up the Swiss tradition of typography.

As a general principle of rationality in reaching conclusions in disputed matters, “Hear both sides” was treated as part of common wisdom by the ancient Greek dramatists. [e.g. Aeschylus, “The Eumenides” 431, 435]

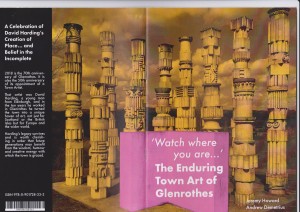

Glenrothes Exhibition October 2018

Introduction

Introduction

Out of the blue, in early 2018, I received an email from Jeremy Howard regarding thoughts and plans he and a few others had of marking the 50thanniversary of my going to work in Glenrothes which also marked the 70thanniversary of the founding of the town. Jeremy and his colleague Andrew Demetrius worked at St. Andrew’s University. It was obvious from our conversations that they had already done a huge amount of research on my work, and the works of colleagues, in Glenrothes. Along with the film-makers, Carolyn Scott and Andy Simm, they were well-advanced in their plans to mount an exhibition later in the year in the town centre of Glenrothes and produce an accompanying film.

These people were all strangers to me and so I was overwhelmed by their efforts and commitment to making all of this happen.

The exhibition, which Andrew and Jeremy put together, took place in October 2018. It was a ‘pop-up’ exhibition in a vacant shop, but this description belies what was an imaginative, beautifully conceived and presented show and catalogue. The latter contains a long, thought-provoking essay. Also presented within the exhibition was the film made by Carolyn and Andy of an interview with me including visits to a number of the works in the town.

By all accounts the exhibition achieved much of what it set out to do along with good attendance numbers and, more importantly, numerous conversations with townsfolk describing their engagements with the works.

Preface to catalogue essay

WATCH WHERE YOU ARE…: The Enduring Town Art of Glenrothes

A Celebration of David Harding’s Creation of Place… and Belief in the Incomplete

2018 is the 70thanniversary of Glenrothes. It is also the 50thanniversary of its appointment of a Town Artist.

That artist was David Harding, a young man from Edinburgh, and in the ten years he worked in Glenrothes he turned the town into a unique haven of art, not just for Scotland or the British Isles but for Europe and the wider world.

Harding’s legacy survives and is worth cherishing in order that future generations may benefit from the wisdom, humour and creative energy with which the town is graced.

On 19 May 2018, a debate took place in the Rothes Halls as part of ReimagiNation festival, which took its title – Glenrothes – A New Day?– from a 1959 public information film, made when the town was barely a decade old. This event followed the similar meetings of previous years in Glenrothes’ larger new town cousins, East Kilbride and Cumbernauld, in which a small panel discussed the past, present and future of the town, and how the spirit of local people and place manifest themselves.

Following the expert opinions, the discussion in the Rothes Halls was opened to the floor, where almost unprompted, the main topic that emerged was the town’s public art and the residents’ overwhelmingly positive feelings for the hippos, mushrooms, poetry and vast range of other sculptural artefacts dispersed throughout the town.

How did this come to be? How did these artworks come to represent the genius lociof the town? Credit must be given to the Glenrothes Development Corporation’s Chief Architect and Planning Officer, Merlyn Williams, and his deputy and successor John Coghill, who together created a position for an artist to work with the architects and other professions in creating the new town environment within the Department of Architecture and Planning.

In May 1968 an advertisement was placed in The Scotsman for an artist or industrial designer, offering a permanent contract, pension, and housing accommodation in return for which the artist would provide “artistic treatment”[i]of the built environment and aid their “determination to build a cultural presence into the architectural evolution of the town.”[ii]

David Harding (b.1937, Leith) has said that the job description was tailor made for him. Previously, he had taught in Scottish schools and worked at a teacher training college in Africa. On returning to Scotland he had received a few commissions but was keen to find a more substantial project to exercise himself and support his young family, and following a successful interview he was offered the post and moved with his wife and children from Edinburgh to Glenrothes.

[i]Glenrothes Development Corporation advertisement, The Scotsman, 3 May 1968

[ii]View From Glenrothes, exhibition catalogue, p.2. Glasgow, Third Eye Centre. 1977

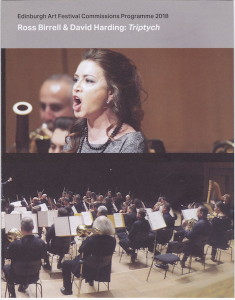

‘Triptych’ – Edinburgh Art Festival – July/August 2018

Ross Birrell & David Harding: Triptych Since 2005, Ross Birrell and David Harding have collaborated on several films and installations which increasingly explore the poetic and political dynamic of music. Triptych, their new work for Edinburgh Art Festival in the historic context of Trinity Apse, is, as the title suggests, tripartite in structure, producing a space where moving image, colour and music correspond and resonate with historical and contemporary architectural, poetic and political contexts. At the heart of Triptych is a three-channel film documenting a performance of Henryk Gorecki’s Symphony No. 3: Symphony of Sorrowful Songs (1976) in the Megaron Concert Hall, Athens. Conceived for documenta 14, the concert was performed by the Athens State Orchestra with the Syrian Expat Philharmonic Orchestra (founded in 2015 by Raed Jazbeh) and featuring Syrian soprano, Racha Rizk. Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs is a moving lament, reflecting the experience of loss as a result of war. A sense of separation and absence pervades the film installation. A central screen documents a wide view of the orchestra and conductor, Daniel Raiskin, while two side panels appear to focus upon an empty space – a space which awaits the solo performance of Rizk. Rizk recites a 15th century lament from the Songs of Lysagora. Sited in the remnants of a 1Sth church, this is one of several contexts that permeate Birrell and Harding’s Triptych. ln its formal presentation, the film references another triptych – Hugo Van der Goes’ Trinity Altarpiece (1478-79), painted for the original Trinity Church and now housed in the National Gallery of Scotland. Alongside Gorecki, the Athens concert also included a performance of Fugue, a project developed by Ross Birrell in collaboration with the Syrian composer and violinist, Ali Moraly. Fugue shares the same etymology as refugee, and in an echo of the subject and countersubject which characterizes contrapuntal fugal form, an initial theme was sent by Birrell to Moraly inviting a response which ultimately took the form of Moraly’s Quatrain for Solo Violin after Paul Celan’s Death Fugue. The scores which combine to form Fugue are exhibited as part of Triptych. Visitors to Trinity Apse will be met by an infusion of colour emanating from new compositions created in reds and blues for windows long devoid of their original stained glass. These chromatic mosaics are based on fragments of a further music score which has its origins in lines by the Palestinian poet, Mahmoud Darwish, whose words are transposed into a twelve-tone musical notation and corresponding numerical grid, and subsequently translated into fields of red and blue colour tones. The complex transposition of forms enacted inTriptych – live recital into film, poetry into music, music into colour – corresponds to wider cultural conditions of exile, migration, displacement and fragmentation; and finds echoes in the architectural fabric of Trinitv Apse itself. Trinity Apse is all that remains of the original Trinity Collegiate Church, taken down in 1848 to make way for Waverley Train Station. In an early example of heritage conservation, the stones were numbered with a view to rebuilding the church on an alternative site. Some 30 years later fragments of the choir and a transept were re-erected on the current site to form Trinity Apse. Still bearing evidence of their painted numbers, a visible testament to their displacement and re-siting, the stones of Trinity Apse provide a fitting context for a work reflecting on loss, trauma and exile

‘Keep me like the echo’

A special performance devised by artists Ross Birrell and David Harding for the Scottish Parliament, Saturday 26 August, 6-8pm.

In the final weekend of Edinburgh Art Festival, artists Ross Birrell and David Harding invite Syrian composer and violinist Ali Moraly, soprano Racha Rizk and musicians of the Damascus String Quintet (of the Syrian Expat Philharmonic Orchestra – SEPO) to present a live performance in association with their new artwork for Edinburgh Art Festival.

The concert will feature Ali Moraly performing Quatrain for Solo Violin after Paul Celan’s Death Fugue, a four-part musical work composed for Fugue, a project devised by Moraly and Birrell in response to the shared origins of the words ‘fugue’ and ‘refugee’. In addition, the musicians will perform a selection of works from both Western classical and Syrian traditional music repertoire.

The concert is presented with the support of: the Scottish Government’s Festivals Expo Fund, EventScotland, British Council Scotland, and the Scottish Parliament.

About the artwork:

During their 12 year collaboration, Scottish artists Ross Birrell and David Harding have explored the thresholds between music and politics, poetry and place, composition and colour. Their new project Triptych, made for our 2018 Festival reflects on themes of flight and dispossession through a film installation in the historic setting of Trinity Apse, located in Chalmers Close just off Edinburgh’s High Street. The 3 channel film documents a powerful recital of Henryk Gorecki’s 1976 Symphony No 3: Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, initiated by the artists for documenta 14 and performed in Athens by the Athens State Orchestra with the Syrian Expat Philharmonic Orchestra (SEPO), featuring Syrian soprano Racha Rizk.

Triptych, Trinity Apse, Chalmers Close, 42 High Street, EH1 1SS

26 July – 26 August 2018

Ross Birrell and David Harding

‘Lento’ from Gorecki’s 3rd Symphony

Documenta 14

‘Lento’ performed by the Syrian soprano Racha Rizk from the Athens concert in the Megaron Concert Hall opening Documenta 14, April 2017.

This three channel video is exhibited in Kassel as part of D14 part 2 which opened in June 2017.

Athens Documenta 14 Daybook. Map Booklet

RIZARI PARK

Near the Athens war museum and the Evangelismo Metro Station, a green oasis of exclusively Mediterranean flora is situated between two busy avenues. The plants were bequeathed in 1844 by Giorgios Rizaris, a former member of the Society of Friends, perhaps the most important of the secret associations formed in the struggle for Greece’s independence from the Ottoman Empire. Rizaris’s wish was for a garden in the city centre for the recreation of its youth. David Harding has paved a ‘desire line’ cutting across the park embedding a couplet on love from Samuel Beckett’s 1936 poem Cascando: ‘If you do not love me I shall not be loved. If I do not love you I shall not love.’ Harding’s recent research on Beckett has found a report that noted: ‘New Irish Offshore Patrol Vessels named the Samuel Beckett Class.’ In the past year, the PV Samuel Beckett has been patrolling the sea off the coast of Libya rescuing refugees.

Documenta 14 – Athens and Kassel 2017

‘If you do not love me………………….’

DESIRE LINES – PATH POEM PROPOSAL 2016

Some ‘rough’ pathways are made by people usually across a space where architects/planners have made a right-angled, paved footpath. The paths made by people are ‘desire lines’. I want to find possible, appropriate ‘desire line’ locations in or around the d14 venues in Athens and Kassel. There could be more than one location in both cities. If suitably chosen, and agreed, one or more of these poetic ‘desire lines’ in both cities could remain in situ when d14 has finished.

The text in Greek and English for Athens and German and English for Kassel, is a couplet from the Samuel Beckett love poem, Cascando

‘If you do not love me, I shall not be loved.

If I do not love you, I shall not love.’

It will immediately become apparent that ‘desire lines’ have been made by the movement of peoples from Syria and other parts into Europe and that, what is in short supply, is love. Beckett’s words, written in 1936 to a woman he had fallen in love with, are like a puzzle carrying a certain obscurity as if he could not quite come out and say, ‘I love you’. However he does set up a necessary reciprocation where love is concerned – that we are dependent on each other for love to flourish.

It will immediately become apparent that ‘desire lines’ have been made by the movement of peoples from Syria and other parts into Europe and that, what is in short supply, is love. Beckett’s words, written in 1936 to a woman he had fallen in love with, are like a puzzle carrying a certain obscurity as if he could not quite come out and say, ‘I love you’. However he does set up a necessary reciprocation where love is concerned – that we are dependent on each other for love to flourish.

New, permanent path in Rizari Park Athens.

with Sam Ainsley and Sandy Moffat.

DOCUMENTA 14 – ATHENS & KASSEL 2017

Symphony of Sorrowful Songs

Symphony of Sorrowful Songs

A project by Ross Birrell & David Harding

“The 3rd Symphony of Henryk Gorecki, performed by members of the Athens State Orchestra and the Syrian Expat Philharmonic Orchestra at Megaron – the Athens Concert Hall, offers a response to the widespread suffering caused by the Syrian Civil War.

It is important that the concert is hosted in Greece, a country which has borne witness,

more than any other country in Europe, to the devastating humanitarian impact of the Syrian conflict, a challenge it has met with dignity and generosity whilst simultaneously facing its own economic hardships and political tensions. As artists we humbly respond to weapons of brutality and bloodshed with works of solidarity and beauty. In common with other aesthetic forms, classical music has the capacity to combine emotional power, intellectual vitality, and political resonance and, as such, this concert might offer a legitimate response to an ongoing war. We are grateful to the Athens Concert Hall and the Athens State Orchestra whose hospitality provides a platform for fellow musicians to perform as creative individuals and professionals as opposed to being cast in the collective role of a political problem. We are grateful to the several Syrian musicians who have travelled from across Europe for their generous commitment to the development of this concert. The concert is not offered as a solution to an intractable conflict. But, in the spirit of hospitality, collaboration and co-existence which has shaped its development, we might find the seeds of such solutions in the future. Music is the groundwork of a politics of listening.”

Ross Birrell, David Harding,

invited artists – documenta 14

More information: www.documenta.de

office@documenta.de

documenta 14 ‘ E ( .r ‘,–r. lliil‘:,T‘,-MEGARON